Outside of the Sandman series proper, as the dark but sophisticated corner of Karen Berger’s DC Editorial offices became Vertigo Comics, a troop of writers continued the tales of some of the less prominent members of the Neil Gaiman comics, with titles like The Dreaming and Lucifer and Merv Pumpkinhead, Agent of D.R.E.A.M. (Yes, that last one is a real comic, and it was written by Fables scribe Bill Willingham.) But that would all happen after Sandman ended, as a way to sustain the franchise while Neil Gaiman moved on to become a fancy-pants novelist and screenwriter. Gaiman produced a few Sandman-related books in the years after the series concluded, and, of course, he’s slated for a return engagement with the character in the fall of 2013, but, in total, more issues of Sandman spin off comics were written by people named neither Neil nor Gaiman than were produced in the entirety of the initial run of the series.

However, and this is a big however, DC and Vertigo kept their hands off the Endless. That was reportedly part of Gaiman’s deal with DC, perhaps to the extent that he co-owns those characters and no one else can do anything with them without his permission, or maybe just as a way to keep Gaiman happy in the hopes that he would one day return to write the characters and bring a gigantic fanbase along with him. (Which, as it seems, has worked out according to plan, if the online gushing about new Gaiman Sandman issues next year was any indication of the fanbase’s gigantism.)

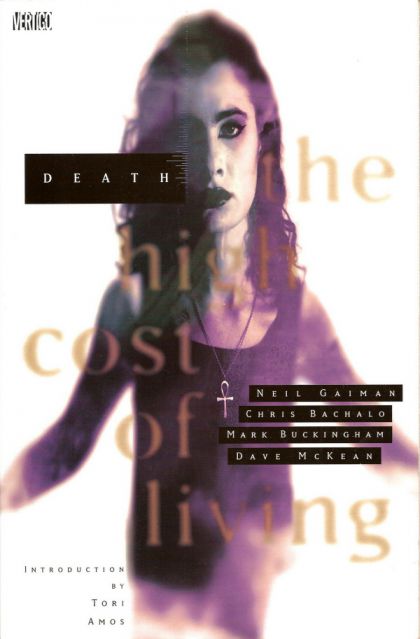

So Dream, Destiny, Desire, Delirium, Destruction, Despair, and Death…well, maybe not Destiny as he’d been around awhile already, but the others…they are Gaiman’s alone to write, except when he loans them out to others to play with, like he presumably did for Jill Thompson’s Little Endless books or that time Paul Cornell had Lex Luthor face down Death in Action Comics a couple of years back. So the first guy to get a crack at a solo Death story was, of course, Gaiman himself, who wrote the three-issues of Death: The High Cost of Living just in time for it to become the first original series ever released under the Vertigo banner.

The first Death miniseries features a reluctant antihero by the name of Sexton—who is an antihero in the traditional sense of having no particularly spectacular qualities, not an antihero in the sense of, say, the Punisher—and a young Goth girl named Didi, who believes that she is the personification of death. Because she is. She’s Death in mortal form, which, according to Gaiman’s own Sandman mythology, occurs once every 100 years. So that’s that.

Unlike the majority of this Sandman reread, I hadn’t even glanced back at Death: The High Cost of Living since the day the final issue came out. I never went back and reread all three issues, and even though I own the Absolute Death hardcover collection, I didn’t crack it open until I sat down to read it for this project. So while my reaction to some of the other Sandman tales may have changed over the years, at least I had fully engaged that work as a whole on several occasions over the past two decades. Not so much with the Death miniseries. It was read in single issues, filed away, and all that I remembered about it was that it was a nice little story about Death teaching someone to appreciate life.

It turns out, that’s not exactly what it is.

Sure, to some extent, all the Neil Gaiman stories that involve the manic pixie Death girl are about the beauty of life, but my memory was that Death: The High Cost of Living was an uplifting, inspirational tale. Like Chicken Soup from Neil Gaiman’s Soul or something. That’s probably why I never went back to it, even though I liked it just fine.

Yet the first Death miniseries doesn’t end with a Sexton opening his arms up to the sun and embracing the wondrous nature of life. His epiphany is more subtle, but no less grand. He simply understands that life is. His final commentary on the subject of death—and at the beginning of the story, he was crafting his own suicide note—is that he wishes that there might be a reality in which Death was “funny, and friendly, and nice. And maybe just a tiny bit crazy.” And he wishes to see her again, but “if that means dying first…” well, he decides he can wait a little bit.

He isn’t a carpe diem kind of young man. But he accepts that life is something, and death is something else, and he saw things in his three issues with Didi that made him scared and showed him kindness and gave him a perspective on something bigger than his small apartment. Sexton is the protagonist, he grows and changes, fundamentally, but not in an overdramatic way. And not because he turns from a meek nonparticipant in the world into an action hero. No, Gaiman keeps the story relatively small, with weirdness at its edges, and that’s enough—along with Didi’s joyous embrace of everything that comes her way—to make him see that there is something precious to this mortal existence. But he doesn’t revel in it. He doesn’t kiss babies or frolic in the flowers. This isn’t Harold and Maude, though the underlying theme is similar. Gaiman keeps the story restrained, focused not on Sexton’s growth as a character but on the dangers faced by the characters, and the quest to find Mad Hettie’s heart.

Mad Hettie, 250 year old bag lady of mystery and strange magic, had appeared in the Sandman series before. But she’s the mechanism that kicks off the plot here. She’s looking for her heart, whatever that means, and Didi aims to find it. Sexton’s along for the ride, mostly because he has a crush on Didi, and that’s enough. Foxglove, from A Game of You, also appears as a singer/songwriter whose experiences with the death of her friends inform her lyrics, and her melancholy melodies become a kind of soundtrack for the series, even though she only appears on a few pages.

And then there’s Chris Bachalo, who made his professional debut on the pivotal Hector Hall/Jack Kirby Dreamworld issue of Sandman a couple of years earlier, and brings a transitional style to this Death miniseries. This was the phase of his career when he was moving from the gritty, scratchy linework toward a more geometric approach to figure drawing and page layout. Mark Buckingham’s inking softened his line up a bit on the story, but you can already see some of the shapes (in faces, in the sequencing of small panels) that would dominate his style by the mid-to-late 1990s. And that’s something my memory got wrong about this miniseries as well. I pictured it as late-phase Bachalo, design-oriented and beautifully rounded, with sharp blacks and soft curves. But it’s not. That was the second, much later, Death miniseries I was recalling and jamming it together with this one in my mind. No, this one features an in-between Bachalo, and that makes it much harsher and less refined, which adds to the gritty reality of Sexton’s internal and external struggles. It’s a messy world, defined by Bachalo’s pencils, and that helps to make the subtle triumph in the end all the more defiant.

Mad Hettie does get her heart back in the end—a golden locket on a chain, hidden inside a nesting doll. It glitters in the sunlight as she shuffles off down the street. Darkness closes in for the final few panels, as the old lady talks to herself about the advice she could have gotten from Death, if she’d been able to stick around.

“Give her time,” says Mad Hettie. “She’ll be back….”

True. Always.

NEXT TIME: Strangers from distant lands meet At World’s End.

Tim Callahan would like to point out that he really does like Harold and Maude and if you want to be free, well, just…be free. Sing out, too, if that’s your thing.